Naeyc the Role of Phonological and Phonemic Awareness in Reading Development

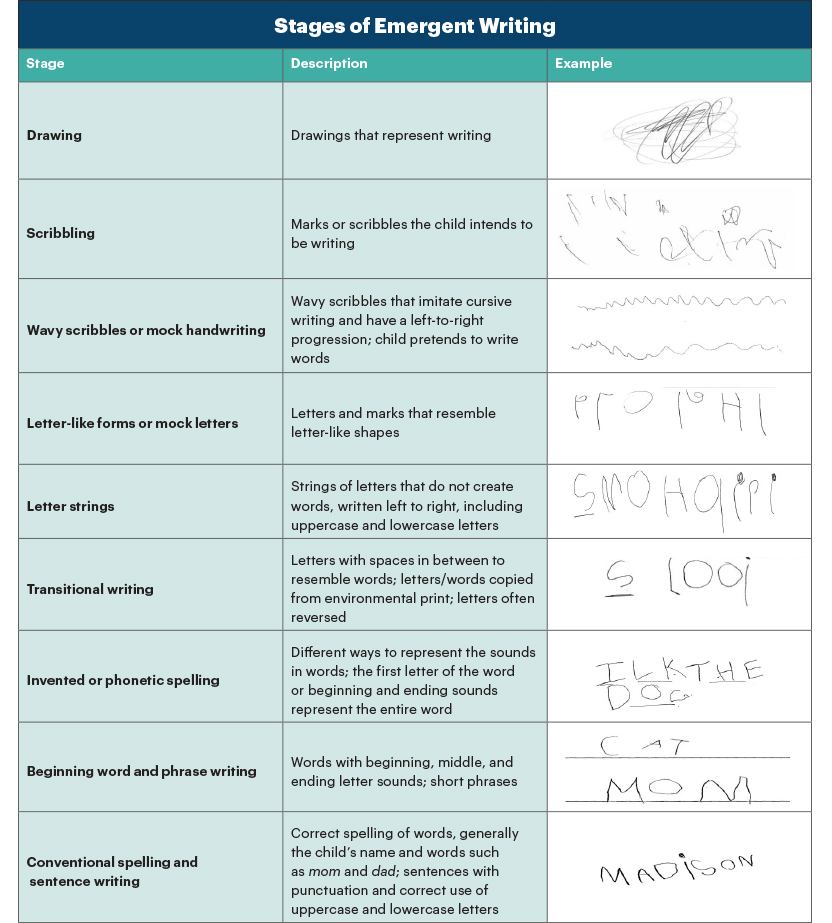

Emergent writing is young children's kickoff attempts at the writing process. Children as young as two years quondam begin to imitate the act of writing past creating drawings and symbolic markings that stand for their thoughts and ideas (Rowe & Neitzel 2010; Dennis & Votteler 2013). This is the get-go of a serial of stages that children progress through equally they learn to write (see "Stages of Emergent Writing"). Emergent writing skills, such as the development of namewriting proficiency, are important predictors of children's future reading and writing skills (National Center for Family & Literacy 2008; Puranik & Lonigan 2012).

Teachers play an important role in the development of 3- to 5-year-olds' emergent writing by encouraging children to communicate their thoughts and record their ideas (Hall et al. 2015). In some early childhood classrooms, yet, emergent writing experiences are almost nonexistent. One recent study, which is in accord with before research, found that 4- and v-year-olds (spread beyond 81 classrooms) averaged only 2 minutes a mean solar day either writing or being taught writing (Pelatti et al. 2014). This article shares a framework for understanding emergent writing and ties the framework to differentiating immature children'south emergent writing experiences.

Agreement emergent writing

Researchers and educators oftentimes use the term emergent literacy to ascertain a wide set of language and literacy skills focused primarily on the evolution and significance of emergent reading skills. To better empathise writing development—and to support teachers' work with young children—researchers have proposed a framework to explain emergent writing practices (Puranik & Lonigan 2014). The framework is composed of three domains: conceptual cognition, procedural knowledge, and generative knowledge.

Conceptual cognition includes learning the function of writing. In this domain, young children acquire that writing has a purpose and that print is meaningful (i.eastward., it communicates ideas, stories, and facts). For case, young children become aware that the reddish street sign says Stop and the letters under the yellow arch spell McDonald's. They recognize that certain symbols, logos, and markings take specific meanings (Wu 2009).

Procedural knowledge is the mechanics of letter and word writing (e.g., name writing) and includes spelling and gaining alphabet cognition. Learning the alphabetic lawmaking (including how to form letters and the sounds associated with each letter of the alphabet) is an essential component of gaining procedural cognition. Children benefit from having multiple opportunities throughout the day to develop fine motor skills and finger dexterity using a variety of manipulatives (e.g., magnetic letters, pegboards) and writing implements.

Generative knowledge describes children's abilities to write phrases and sentences that convey meaning. It is the ability to translate thoughts into writing that goes beyond the give-and-take level (Puranik & Lonigan 2014). During early babyhood, teachers are laying the foundation for generative noesis as children learn to limited themselves orally and experiment with unlike forms of written advice, such as composing a story, writing notes, creating lists, and taking letters. Children can dictate words, phrases, or sentences that an adult can record on paper, or they can share ideas for grouping writing.

Developing conceptual, procedural, and generative cognition of writing

Children gain knowledge of and involvement in writing equally they are continually exposed to print and writing in their surround. At that place are multiple strategies teachers can use to scaffold children's writing, such as verbally reminding children to use writing in their classroom activities and providing advisable writing instructions (Gerde, Bingham, & Wasik 2012). By beingness aware of children's electric current fine motor abilities and their progress in emergent writing, teachers tin can use a mix of strategies to foster growth in each kid'south zone of proximal development (Vygotsky 1978).

Practicing name writing

One of the first words children commonly learn to write is their first name (Both-de Vries & Bus 2008). Name writing increases children's conceptual and procedural knowledge. Names are meaningful to children, and preschoolers typically are interested in learning to write the letters in their name, specially the first letter (Both-de Vries & Bus 2008). Namewriting proficiency provides a foundation for other literacy knowledge and skills; it is associated with alphabet knowledge, alphabetic character writing, print concepts, and spelling (Cabell et al. 2009; Drouin & Harmon 2009; Puranik & Lonigan 2012).

Preschoolers benefit from daily writing experiences, so it is helpful to embed writing in the daily routine, such every bit having children write (or attempt to write) their names at sign-in and during choice times. Be sensitive to preschoolers' varying levels of fine motor skills and promote the joy of experimenting with the fine art of writing, regardless of a child's current skill level. Encourage invented spelling (Ouellette & Sénéchal 2017) and attempts at writing letters or letter-similar symbols.

As Ms. Han'south preschoolers enter the classroom, they sign in, with parental support, past writing their names on a whiteboard at the classroom entrance. Children in Ms. Noel's classroom go to a special table and sign in as they enter the room. Ms. Patel instructs her preschoolers to answer the question of the twenty-four hours by writing their names under their called answers. Today, the children write their names to answer the question "What are your favorite pocket-size animals—piglets, ducklings, or kittens?" Juan and Maria help their friends read the question and write their names under the advisable headings. Pedro writes Pdr under the piglets heading, Anthony writes his complete name nether ducklings, and Tess writes the letter T under kittens. In Mr. Ryan's class, children write their names during dissimilar activities. Today, children sign in as they pretend to visit the dr. in ane learning center and sign for a package commitment in another. Meanwhile, Tommy walks effectually the room asking other preschoolers to sign their names in the autograph volume he created in the writing centre.

Tips for teachers

- Develop a sign-in or sign-out routine that allows children to write, or attempt to write, their names each day. In some classrooms, or for some children, the routine may brainstorm with writing the start letter of the alphabet instead of the whole proper noun or with scribbling letterlike symbols.

- Use peer helpers to aid children with the name-writing process.

- Model writing your name and promote proper noun-writing activities in several centers through the 24-hour interval, such as having children sign their proper name equally they write a prescription or when they complete a painting.

Learning from instructor modeling

Children benefit from teachers modeling writing and from opportunities to interact with others on writing projects. Teachers can connect writing to topics of interest, call up aloud virtually the process of composing a bulletin (Dennis & Votteler 2013), and explain how to programme what to write (e.g., choosing words and topics, along with the mechanics of writing, such as punctuation). Children struggling to attain early writing skills do good from explicit teaching (Hall et al. 2015). Teach children that messages create words and words create sentences. Employ environmental print (e.g., labels, charts, signs, toy packaging, clothing, and billboards) to assistance children realize that impress is meaningful and functional (Neumann, Hood, & Ford 2013). These types of activities build both conceptual and procedural noesis.

Children benefit from teachers modeling writing and from opportunities to interact with others on writing projects. Teachers can connect writing to topics of interest, call up aloud virtually the process of composing a bulletin (Dennis & Votteler 2013), and explain how to programme what to write (e.g., choosing words and topics, along with the mechanics of writing, such as punctuation). Children struggling to attain early writing skills do good from explicit teaching (Hall et al. 2015). Teach children that messages create words and words create sentences. Employ environmental print (e.g., labels, charts, signs, toy packaging, clothing, and billboards) to assistance children realize that impress is meaningful and functional (Neumann, Hood, & Ford 2013). These types of activities build both conceptual and procedural noesis.

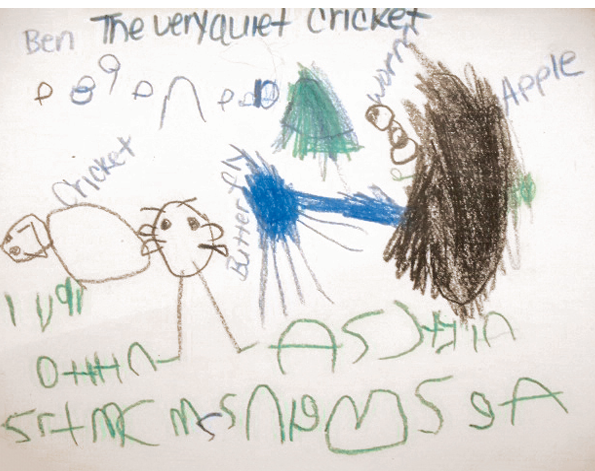

When Ms. Noel sits with the children during snack, she talks with them most the dissimilar foods they similar to consume. Ben tells her he likes chicken. She writes on a small whiteboard, "Ben likes craven." She asks Ben to read the phrase to a friend. Later, Ben writes the phrase himself.

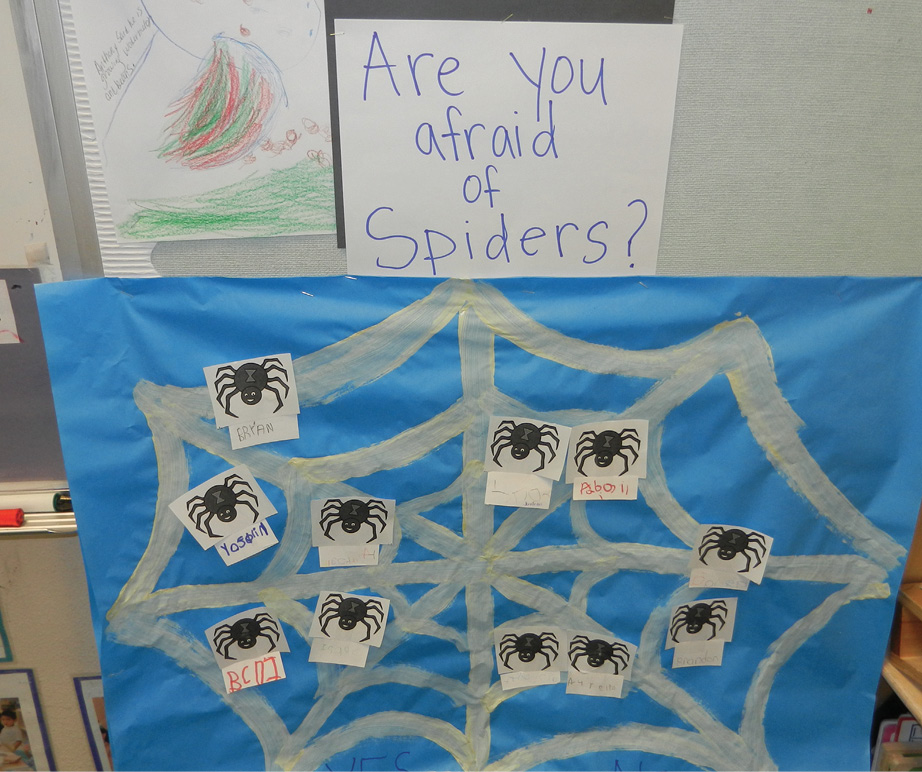

Mr. Ryan conducts a sticky notation poll. He creates a giant spiderweb and writes the question, "Are you lot afraid of spiders? Aye or no." He gives the children gummy notes so each tin can write either aye or no and and so place it on the giant web. This activeness is followed by a give-and-take of spiders.

Tips for teachers

- Explicitly model writing by showing the writing procedure to children and thinking aloud while writing. Instead of writing the question of the day or the forenoon message before the children go far, write it in front of them.

- Label specific items in the room, and describe children's attention to the written words. Write out functional phrases on signs related to routines, such as "Take three crackers" or "Launder easily before eating," and so read and display the signs.

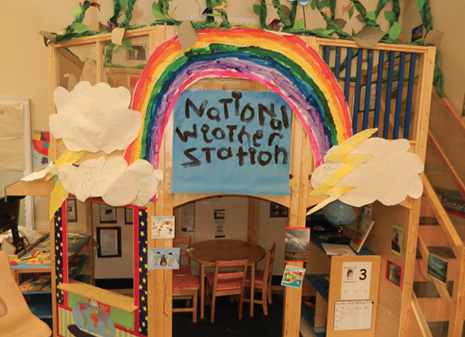

- Take the children paint large classroom signs related to themes being explored, such as the National Conditions Station, Snack Bar, Public Library, or Entomology Heart.

Writing throughout the day

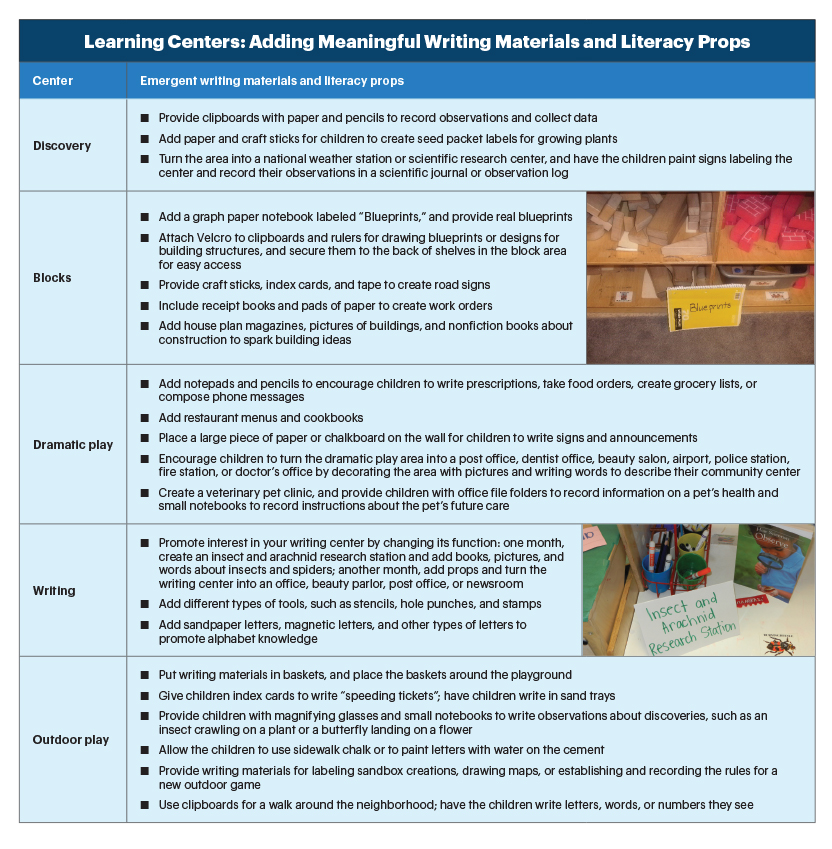

Preschoolers bask experimenting with the writing process. Emergent writing experiences can include spontaneous writing during center time and teacherguided writing activities. Writing can become an important component of every learning eye in the preschool classroom (Pool & Carter 2011), specially if teachers strategically place a variety of writing materials throughout the classroom and offer specific guidance on using the materials (Mayer 2007). (Run into "Learning Centers: Adding Meaningful Writing Materials and Literacy Props.")

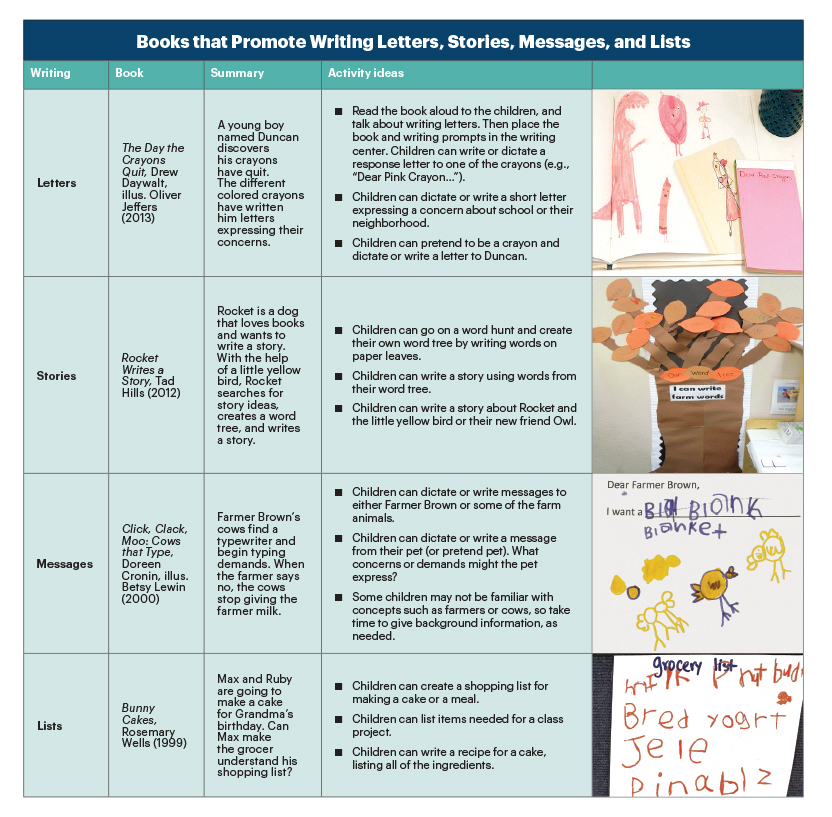

Teachers can intentionally promote peer-to-peer scaffolding by having children participate in collaborative writing experiences. Read-alouds are also a wonderful ways of promoting writing; there are a number of stories that feature characters in books writing letters, stories, messages, and lists (run across "Books That Promote Writing"). Model writing stories, making lists, or labeling objects, and so encourage your preschoolers to write a response letter to a character in a story, create their own storybook, or write a wish list or a shopping list. Such a variety of writing experiences will too build their generative knowledge of writing.

Ms. Han has strategically placed a multifariousness of writing materials throughout the classroom—a scientific journal in the discovery area and so children can tape their observations and ideas; a graph newspaper notebook in the block expanse for drafting blueprints with designs and words; and a receipt book, newspaper, and markers in the dramatic play area. Savannah sits at the discovery center looking at a classroom experiment. Ms. Han asks, "Savannah, could you write about your observations in our science journal?" Savannah begins writing in the journal.

Three boys are playing in the cake area. Ms. Han asks, "What are y'all edifice?" Marcus replies, "We are going to build a rocket transport." Ms. Han says, "Could y'all create a blueprint of your rocket and then build it?" The boys eagerly begin drawing a plan. Several children in the dramatic play middle are drawing unlike types of flowers for a flower marketplace. Ms. Han says, "In a flower marketplace, signs tell customers what is for sale and how much it costs. Would you similar to create some signs?" The children readily agree and offset to create signs.

Tips for teachers

Tips for teachers

- Strategically identify writing materials, such as sticky notes, modest chalkboards, whiteboards, envelopes, clipboards, journals, stencils, golf game pencils, markers, and diverse types, sizes, and colors of paper throughout the classroom.

- Provide specific teacher guidance to scaffold children'due south writing. While some children may be off and running with an open-ended question, others might be improve supported if the teacher helps write their ideas—at least to get them started.

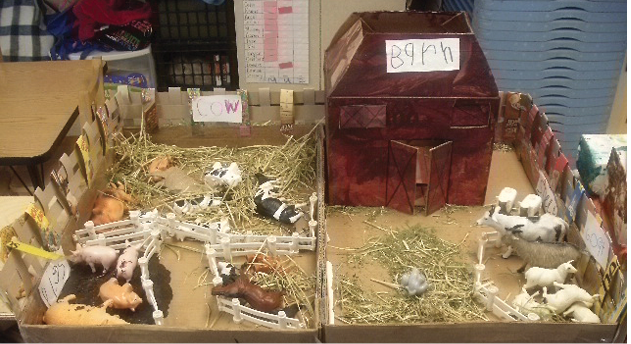

- Create writing opportunities connected to your current classroom themes or topics of involvement. Involve the children in collaborative writing projects, such equally creating a diorama afterward a farm visit and making labels for the different animals and the barn. With teacher support, the class could also develop a narrative to describe their farm visit.

Abode–school connexion

Both preschool writing instruction and domicile writing experiences are essential components of helping children develop writing skills. A major advantage of the habitation– school connexion is that children see the value of what they learn in schoolhouse when parents actively participate in the aforementioned type of activities at habitation. Teachers can encourage parents to brandish photos of their kid engaged in writing activities at domicile and to share samples of their kid's writing or drawings from home to inform instruction (Schickedanz & Casbergue 2009). To maximize parental involvement and support, teachers should be sensitive to the diversity of the families in their programs and exist inclusive past promoting writing in children'south dwelling languages. These experiences tin can help promote children'due south conceptual, procedural, and generative knowledge.

Both preschool writing instruction and domicile writing experiences are essential components of helping children develop writing skills. A major advantage of the habitation– school connexion is that children see the value of what they learn in schoolhouse when parents actively participate in the aforementioned type of activities at habitation. Teachers can encourage parents to brandish photos of their kid engaged in writing activities at domicile and to share samples of their kid's writing or drawings from home to inform instruction (Schickedanz & Casbergue 2009). To maximize parental involvement and support, teachers should be sensitive to the diversity of the families in their programs and exist inclusive past promoting writing in children'south dwelling languages. These experiences tin can help promote children'due south conceptual, procedural, and generative knowledge.

Ms. Noel wants to strengthen domicile–school connections with the families in her program. She decides to introduce the children to Chester (a stuffed teddy bear). She tells the children that Chester wants to acquire more near what the children exercise at home and to go on some weekend adventures. She says, "Each weekend, Chester will travel home with a child in our class. During the time Chester stays at your house, take pictures of the activities yous do with Chester and write most them in the Chester Weekend Adventures journal. At the beginning of the week, bring Chester and the journal dorsum to school to share what you did. We will put Chester and the journal in the classroom library when he is not on a visit, so everyone can run across where he has been." The children are excited about taking Chester home and writing about their adventures.

Tips for teachers

- Find writing opportunities that strengthen home–school connections. For example, encourage families to create books at home related to a detail theme or a specific topic. Invite children to share their books with the class and then add together them to the library.

- Invite families to share the types of writing activities their children appoint in at home. Encourage parents to plant routines that include writing lists, messages, stories, and letters.

- Give families postcards to mail to friends in other states and countries. Take them ask their friends to postal service a answer to the preschool class. Create a display of the render messages and postcards.

Summary

Teachers play an of import role in promoting emergent writing development by scaffolding writing activities that engage young children in edifice their conceptual, procedural, and generative knowledge. Writing can easily be embedded in daily routines equally children write their names, engage in learning centers, practice writing for a purpose based on teacher and peer models, and contribute to group writing activities. Be intentional during interactions with children and comprise all-time practices. Promote the evolution of emergent writing—and emergent literacy—by implementing purposeful strategies that encourage writing in the classroom and at dwelling. Teachers who provide young children with a various array of early on writing experiences lay the foundation for kindergarten readiness.

Authors' note: A special thank you to all of the teachers who participated in the Striving Readers Literacy Program and shared their literacy ideas. Thanks to Barbara Berrios for sharing the Chester Bear thought.

References

Both-de Vries, A.C., & A.G. Motorcoach. 2008. "Name Writing: A Start Step to Phonetic Writing? Does the Proper noun Have a Special Role in Understanding the Symbolic Function of Writing?" Literacy Education and Learning 12 (2): 37–55.

Cabell, Southward.Q., L.M. Justice, T.A. Zucker, & A.S. McGinty. 2009. "Emergent Name-Writing Abilities of Preschool-Age Children with Linguistic communication Damage." Language, Speech communication, and Hearing Services in Schools twoscore (1): 53–66.

Dennis, L.R., & N.Thou. Votteler. 2013. "Preschool Teachers and Children's Emergent Writing: Supporting Diverse Learners." Early on Childhood Education Journal 41 (vi): 439–46.

Drouin, M., & J. Harmon. 2009. "Name Writing and Alphabetic character Knowledge in Preschoolers: Incongruities in Skills and the Usefulness of Name Writing as a Developmental Indicator." Early Childhood Research Quarterly 24 (3): 263–70.

Gerde, H.K., G.E. Bingham, & B.A. Wasik. 2012. "Writing in Early Childhood Classrooms: Guidance for All-time Practices." Early Babyhood Education Journal 40 (six): 351–59.

Hall, A.H., A. Simpson, Y. Guo, & S. Wang. 2015. "Examining the Effects of Preschool Writing Instruction on Emergent Literacy Skills: A Systematic Review of the Literature." Literacy Research and Instruction 54 (2): 115–34.

Mayer, Grand. 2007. "Emerging Knowledge nearly Emergent Writing." Young Children 62 (ane): 34–41.

National Center for Family Literacy. 2008. Developing Early on Literacy: A Scientific Synthesis of Early on Literacy Development and Implications for Intervention. Written report of the National Early Literacy Panel. Washington, DC: National Institute for Literacy.

Neumann, M.K., M. Hood, & R.One thousand. Ford. 2013. "Using Environmental Print to Enhance Emergent Literacy and Print Motivation." Reading and Writing 26 (five): 771–93.

Ouellette, G., & Grand. Sénéchal. 2017. "Invented Spelling in Kindergarten as a Predictor of Reading and Spelling in Course 1: A New Pathway to Literacy, or Just the Same Road, Less Known?" Developmental Psychology 53 (1): 77–88.

Pelatti, C.Y., S.B. Piasta, L.One thousand. Justice, & A. O'Connell. 2014. "Language- and Literacy-Learning Opportunities in Early Childhood Classrooms: Children'southward Typical Experiences and Within-Classroom Variability." Early Babyhood Research Quarterly 29 (4): 445–56.

Pool, J.Fifty., & D.R. Carter. 2011. "Creating Print-Rich Learning Centers." Didactics Young Children 4 (4): xviii–20.

Puranik, C.S., & C.J. Lonigan. 2012. "Proper noun-Writing Proficiency, Non Length of Proper noun, Is Associated with Preschool Children's Emergent Literacy Skills." Early Childhood Enquiry Quarterly 27 (2): 284–94.

Puranik, C.S., & C.J. Lonigan. 2014. "Emergent Writing in Preschoolers: Preliminary Testify for a Theoretical Framework." Reading Enquiry Quarterly 49 (4): 453–67.

Rowe, D.Westward., & C. Neitzel. 2010. "Interest and Bureau in 2- and 3-Year-Olds' Participation in Emergent Writing." Reading Research Quarterly 45 (2): 169–95.

Schickedanz, J.A., & R.M. Casbergue. 2009. Writing in Preschool: Learning to Orchestrate Meaning and Marks. 2d ed. Preschool Literacy Collection. Newark, DE: International Reading Clan.

Vygotsky, 50.S. 1978. Heed in Order: The Evolution of Higher Psychological Processes. Ed. & trans. M. Cole, 5. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & Due east. Souberman. Rev. ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wu, L.Y. 2009. "Children's Graphical Representations and Emergent Writing: Testify from Children's Drawings." Early Child Development and Intendance 179 (1): 69–79.

Photographs: pp. 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, eighty, courtesy of the authors; p. 74, © iStock

Naeyc the Role of Phonological and Phonemic Awareness in Reading Development

Source: https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/nov2017/emergent-writing

0 Response to "Naeyc the Role of Phonological and Phonemic Awareness in Reading Development"

Post a Comment